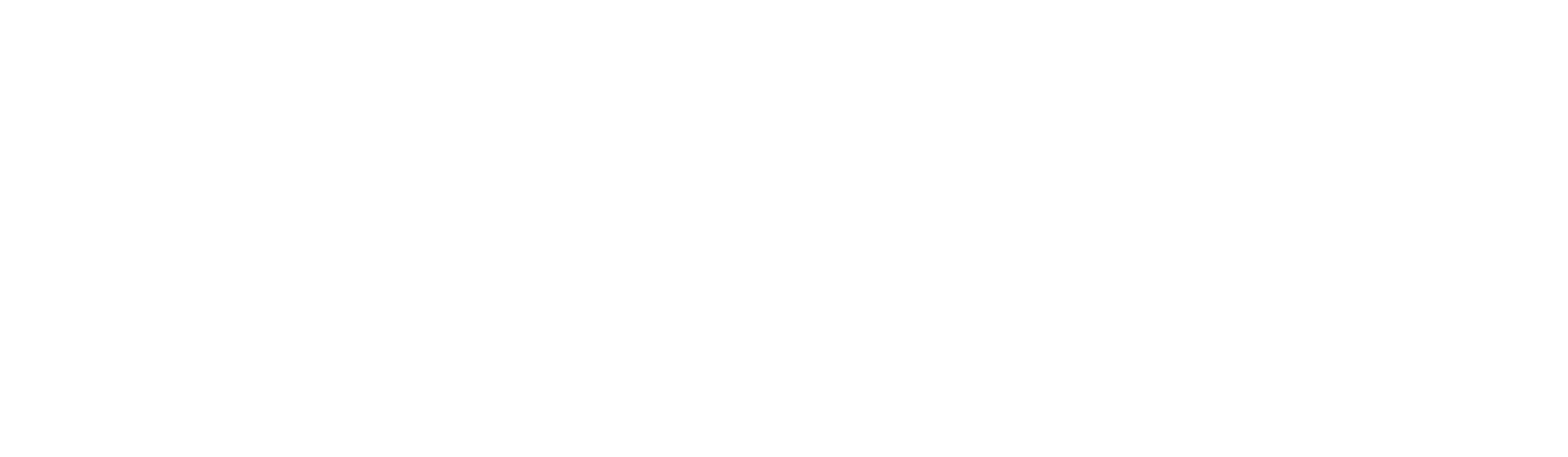

Captivated by the ancient atmosphere of Washington Square and its environs, architect Charles Follen McKim and writer Henry James in written, photographic and built form viewed the 18th century town as a venerable spot, a place firmly in the lexicon of America’s foundation myth and an inspiration for their own romantic views, where the past could inform the present.

The Architect’s View

Relief portrait of Charles Follen McKim by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, 1878. (National Portrait Gallery)

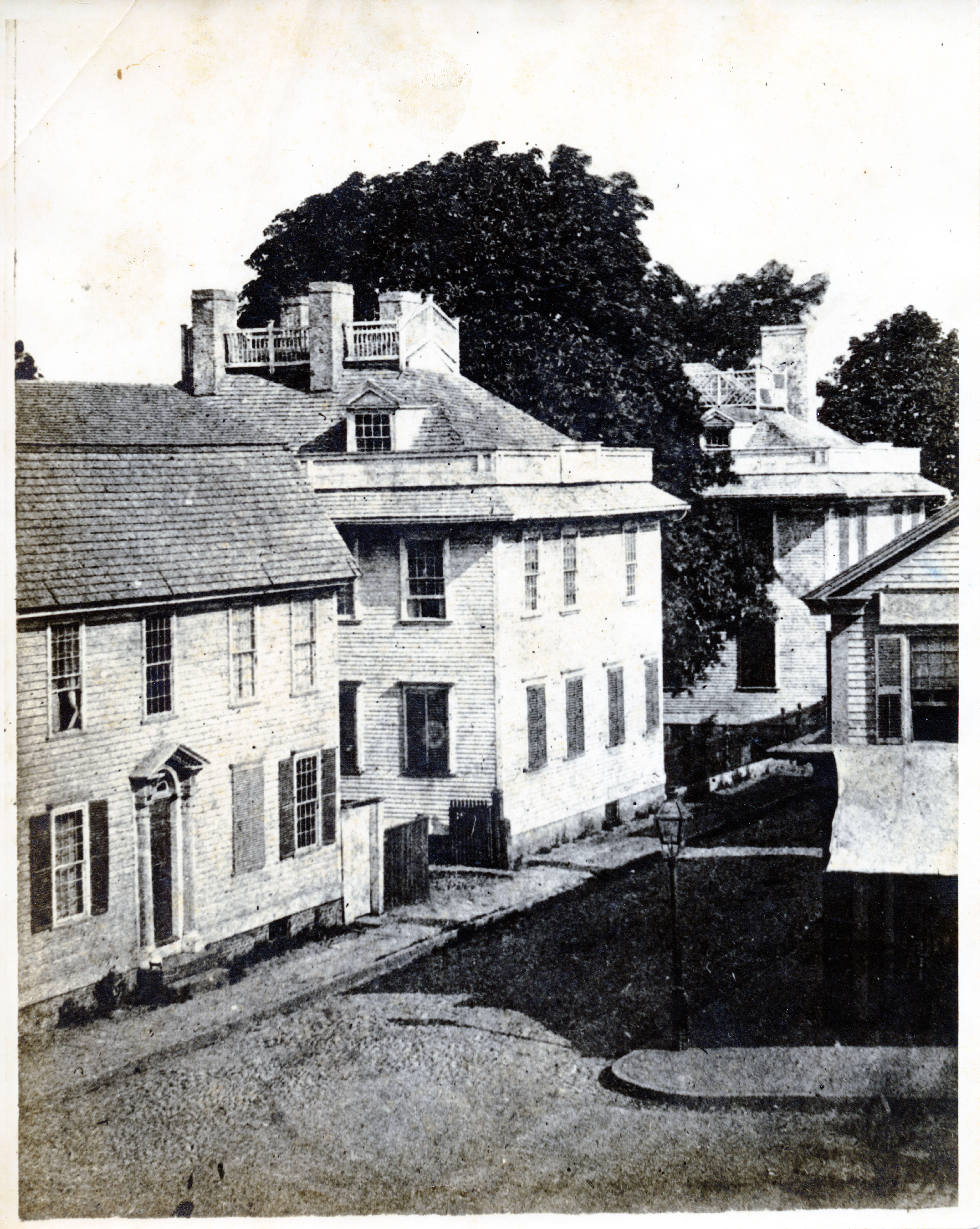

Charles Follen McKim, the third American to be educated in architecture at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, saw the value of Newport’s old streets and buildings. With his classical training and eye for architectural form, he appreciated the historical layers of Newport’s past. In 1874, he commissioned a series of photographs to record 18th century streetscapes and structures. As the nation approached its Centennial in 1876, Newport served as a powerful site of inspiration for the Colonial Revival. Many other architects, writers, poets and painters began to admire the intimate scale and historical layers of the city, which appealed to their picturesque sensibilities.

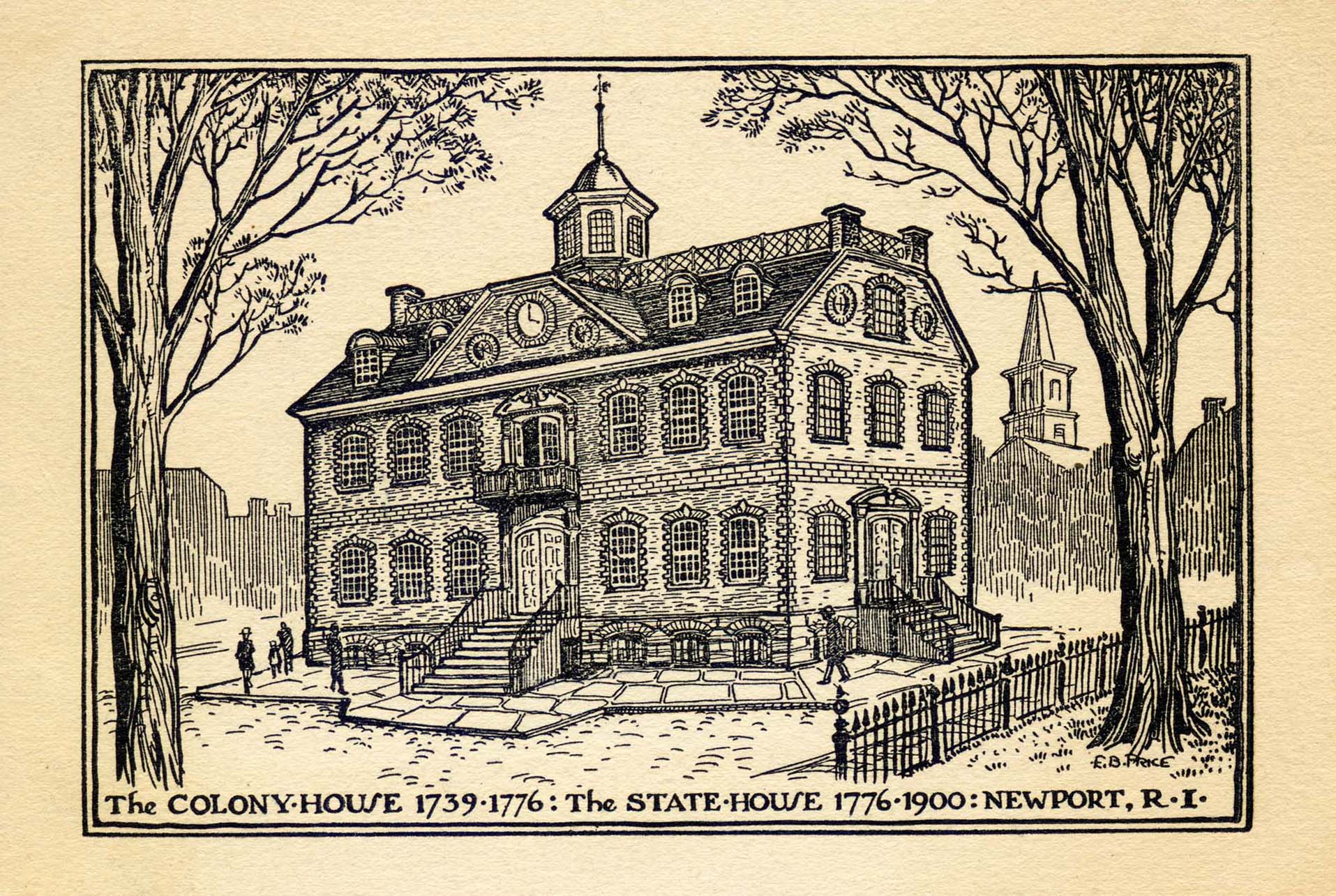

The cupola of the Colony House (1739) rises above the varied mixture of roof types, chimneys, and multiple additions in the picturesque massing of colonial buildings. The asymmetrical skylines and textured shingled facades of these 18th century streetscapes inspired Charles Follen McKim’s work in the Colonial Revival style during the 1870s and 1880s.

The Writer’s View

Portrait of Henry James by John La Farge, 1862. (Century Association)

Henry James viewed Washington Square as the mellowed remnant of a golden past. He wrote of Newport in a painterly way, using color, light, perspective and the moods they evoke, comparing Washington Square and the Colony House to old Dutch paintings.

I have been quite awe-struck by the ancient State House (the Colony House of 1741) that overlooks the ancient Parade, and edifice ample, majestic, archaic, of the finest proportions and full of a certain public Dutch dignity. . . Here was the charming impression of a treasure of antiquity. . . the wide, cobbly, sleepy space. . . in the shadow of the State House, must have been much more of a Van der Heyden, or somebody of that sort than one could have dreamed.

— Henry James, The Sense of Newport, 1906

James’ roving eye was continually enchanted by the intimate scale of the 18th century streets, the textured wood and red toned brick of aged buildings aglow in afternoon sun, richly carved Georgian doors adding a flourish of ornament to severe facades, soaring chimneys marking the skyline and lush greenery cascading over the wall of an intimate urban garden. Here, for the writer, was a venerable treasured place.

What indeed but very old ladies did they resemble, the little very old streets? . . . In this mild town corner, when it ws so indicated that the grass should be growing between the primitive paving stones, and where indeed I honestly think it mainly is, whatever remains of them, ancient peace had appeared formerly to reign — though attended by the ghost of ancient war, inasmuch as these had indubitably been the haunts of our auxiliary French officers during the Revolution.

— Henry James, The Sense of Newport, 1906

The author imagined the inhabitants of the old city, well aware that cultural voices could and did call out to those who stopped, looked and listened. His writing imbued the urban scene with personality and its own particular psychology of space and emotion. For James, Newport was cast as both a place and a person with distinct character traits. Nobility, bravery, vanity, gluttony and a host of other qualities were elicited by the buildings, lanes and landscapes encountered by the writer on his literal and figurative wanderings.

By the 1890s, the juxtaposition of old and new in Newport became even more striking. Linked to the mainland by train and steamship, Newport was no longer an isolated coastal enclave, but began to flourish as a fashionable destination.

Illustrations by Raymond Crawford Ewer in a 1914 issue of Puck, a satirical English magazine, depicting fashionable life in Newport. (Library of Congress)