Washington Square

Foundations, Revolutions, & Evolutions

︎

1

The Square

Washington Square is a many layered time capsule. Centuries of urban development are embedded in its streets and buildings, from even before the establishment of Newport by European colonists in the 17th century to the present day. It has been a place of settlement, of architectural triumphs, of promenades and parades, of shopkeepers and sailors. Change has been ever present in an evolving urban scene. Colonial merchants’ houses were repurposed as Victorian businesses. Neon signed stores and diners appeared in the square’s 20th century guise. Some things, however, have stood the tests of time. The streets retain their original colonial period layout.

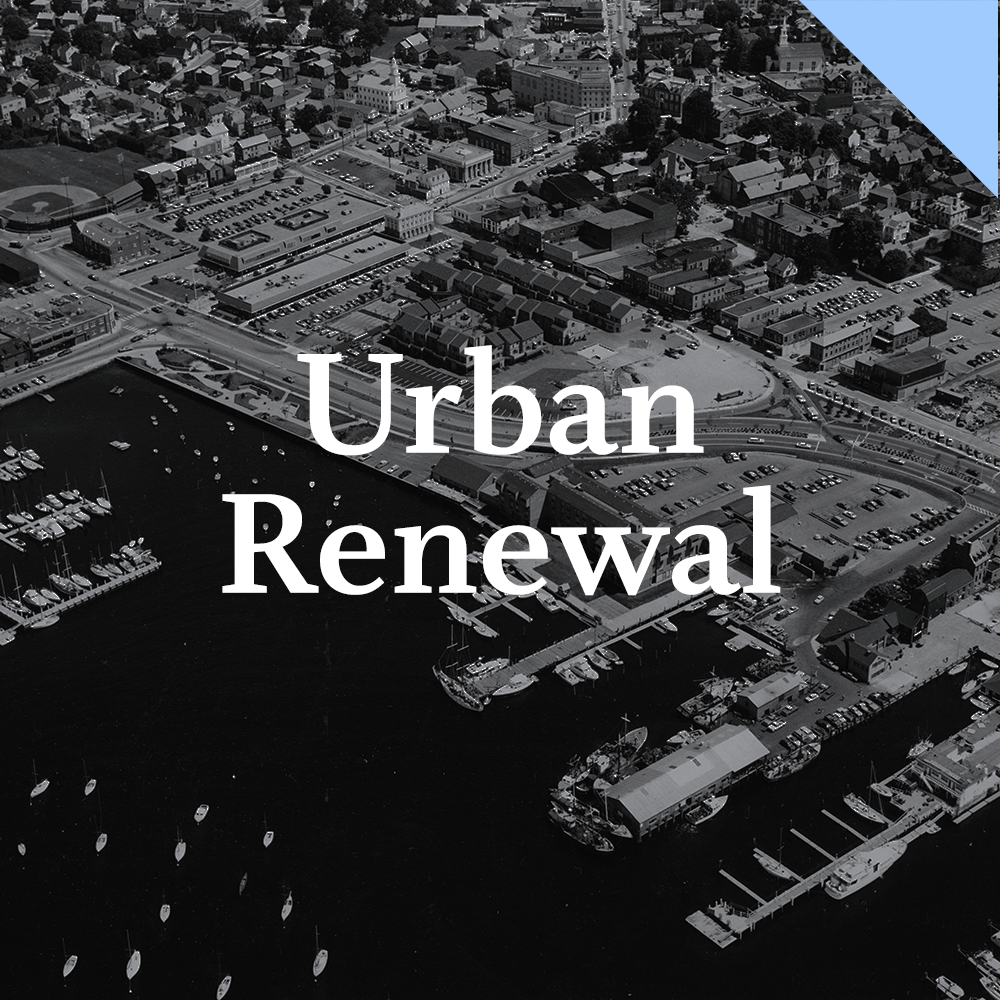

The Colony House (1739) and Brick Market (1762) have remained constant landmarks, witnesses to revolutions, urban renewals and historic revivals. The story of Washington Square is one of an accidental work of urban art. Never subject to a grand vision or master plan, it evolved over the ages reflecting the tastes, temperaments and technologies of each generation. The area was not a formally designed urban space, but evolved from open land eventually referred to in the 18th century as "the Parade." By the early 1760s, the area took its present form as a grand civic space with the completion of the Brick Market, seen at the west end of the square in the images to the left. Following the Revolution, the town rejected references to the British Crown by dispensing with the Queen and Anne Streets, which formed two sides of the triangular shaped park, and renaming the entire urban ensemble Washington Square in 1800. Adjacent to the Brick Market building is Long Wharf Mall, which served as a thoroughfare from the 1680s until urban renewal of the late 1960s, when it was converted into a pedestrian zone.

Views of the square looking east, towards the Colony House

2

Colonial Settlement

Idealism and pragmatism combined to create Newport when, in 1639, a group of colonists settled at the southern tip of Aquidneck Island. Among the leaders of the group were Nicholas Easton, William Coddington, William Brenton, John Clarke, John Coggeshall, Jeremy Clarke, Thomas Hazard, Henry Bull and William Dyer. These founders provided the place names for various points of land, coves and streets in the new settlement, which occupied lands already occupied and cultivated for centuries by Native Americans.

Lay out the streets and lands and to keep all sea banks free for fishing the town of Newport.

— Rhode Island General Assembly, 1640

Following the principles established by Roger Williams with the founding of the Rhode Island Colony, freedom of conscience prevailed in the minds and civic affairs of the settlers while water sources and topography determined the placement of the streets and domiciles. The lack of one dominant religious sect in the life of the community, in contrast to nearby Puritan Massachusetts Bay Colony, produced no house of worship as the focal point of the town.

Here is a medley of most Perswasians butt neither church nor meeting house, except for one built for the use of Quakers, who are very numerous.

— A Short Account of the Present State of New England, 1690

Wharves and steeples define the skyline of the city in this detail from J. P. Newell’s 1884 lithograph, Newport in 1730.

Many of the first colonial settlers built their houses near a spring at the present day intersection of Spring and Touro Streets. Several streams emanated from this water source in the direction of Broad Street, now known as Broadway, and Marlborough Street towards the harbor. In the 1680s several merchants collaborated in the creation of Long Wharf to promote the shipping trade, heralding a burgeoning commercial life. Due to the value of waterfront land, narrow lots ran from the harbor on the west up the hillside to the east. The north/south axis of Thames street extended the entire length of the harbor and every side street terminated at the waterfront.

The sea determined the city’s orientation. Shops and residences increased in number, but there were very few religious structures. While multiple denominations met in the homes of congregants, the freedom to pursue business preoccupied the residents as Newport grew into one of the major seaports of British North America. Sturdily built wharves, houses and warehouses defined the streetscapes of the hard working and entrepreneurial colonial city. Yet, it lacked grandeur. With the increasing mercantile wealth of the ensuing century, all of that would change.

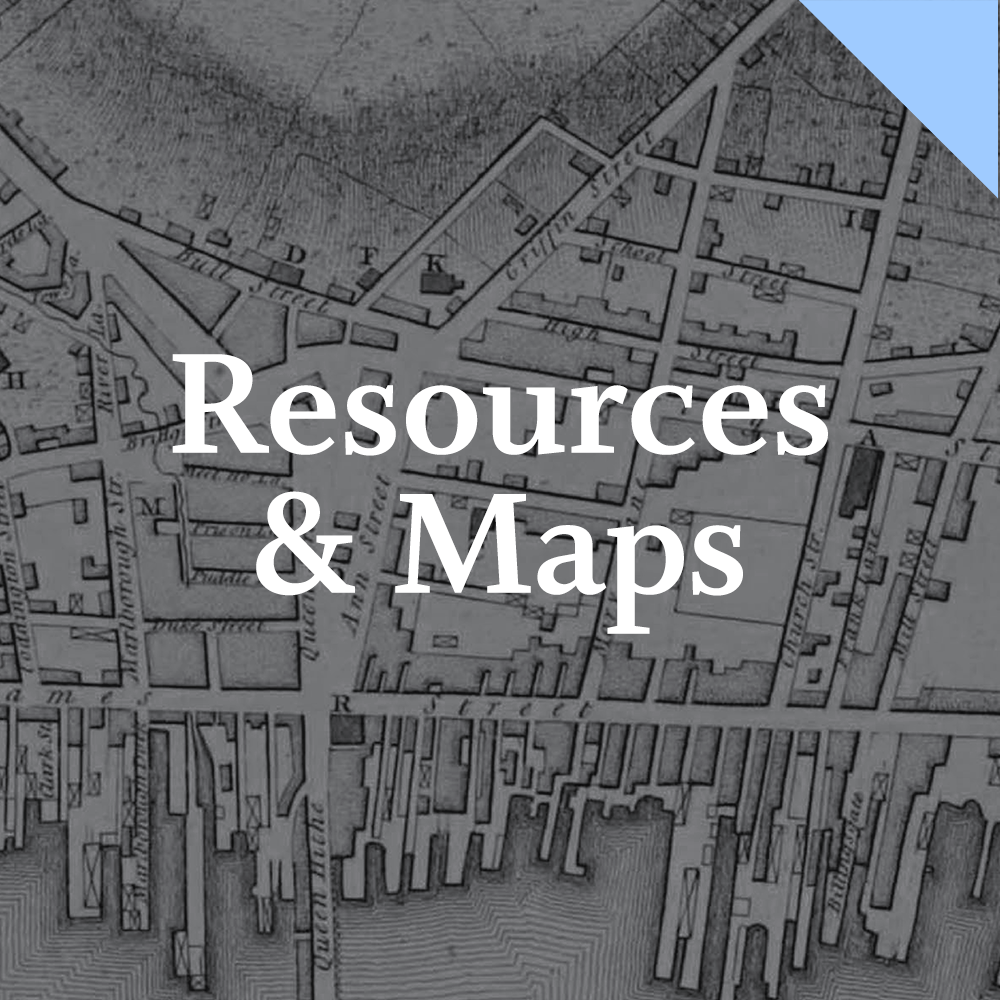

Map detail of Long Wharf, Washington Square, and the site of the Spring

The town had grown to the admiration of all.

— Newport General Council, 1712

3

Evolution & Revolution

Evolution & Revolution

Newport evolved from a modest 17th century community to a mighty 18th century city. In 1712, Newport’s governing council commissioned John Mumford to survey the streets of their fair city. These very thoroughfares became the setting for grand architecture as the 18th century progressed. Unlike Williamsburg, Philadelphia or Savannah, which from inception were formally planned cities focused on squares, parks and public edifices, Newport’s streets were well established by the time construction commenced on large scale architectural projects. Churches, meeting houses and civic buildings had to take their place among the domiciles of merchants, artisans and laborers. Even within such limitations, the effect was exceptional and created a striking display of public grandeur.

Portrait of Ezra Stiles by Samuel King, 1771. (Yale University Art Gallery)

The sense of pride in Newport’s cityscape is evident in the map (below) drawn in 1758 by the Reverend Ezra Stiles, who gave as much attention to public buildings and shops as to the orientation of streets. This eminent theologian and scholar served as the Pastor of the Second Congregational Church, Librarian of Redwood Library, and, later President of Yale University. His approach to the map was not that of a skilled cartographer but as man of the Enlightenment, as one dedicated to recording his environment.

Newport’s system of streets and wharves were fully established by the eve of the American Revolution. Public buildings proclaimed the wealth and increasing cultural sophistication of the inhabitants. This fine metropolis enjoyed the height of commercial success, which came to a drastic end with the onset of war. Occupation by British troops from 1776 to 1779 and the ensuing loss of population substantially impaired the town’s maritime economy and associated enterprises.

Map of Newport by Ezra Stiles, 1858. (Redwood Library & Athenaeum)

Washington Square remained the nucleus of a city that was now surpassed economically by Providence and other ports in the post-war years. Few new streets and even fewer grand buildings appeared on the urban landscape, a symptom of economic stagnation. Only in the 1840s did Newport begin to flourish again with its rise as a summer resort. While the colonial seaport diminished in social and economic importance, Victorian era banks, businesses and streetcars would transform the streetscapes of Washington Square.

4

The Victorian Age

New industrial technology and a taste for the antique played out in the Washington Square of the 19th century. Steamships and trains arrived at Long Wharf while streetcars made their way through the old square. Shops and businesses replaced the grand houses of 18th century merchants in this bustling commercial center. At the same time, painters, illustrators and photographers saw a mythic image of Newport as a romantic place redolent with ghosts of a colonial past and 18th century architecture of noble proportions.

Streetcars were a modern marvel introduced to Newport during a burgeoning industrial age. Not all residents warmly greeted the new form of transportation. The first attempt to establish street rails in the 1860s was a failure, followed by another defeat in 1884. Some summer residents took offense at the incursion the street cars made into their resort enclave. Undaunted, the proponents of mass transit fought on. In 1889, the newly organized Newport Street Railway initiated placement of tracks along Broadway and converging on Washington Square.

It would be annoying to these people to be obliged to move to allow passage of so vulgar and plebian a thing as a horse car.

— The Providence Journal, 1898

While industry and technology introduced modern amenities to Newport's streetscapes in the mid-19th century, painters, architects and writers began to see the city as an historic jewel of mythic proportions. The colonial district, with Washington Square at its heart, appealed to artists seeking the romance of the past in the picturesque assortments of old houses. They took what may rightly be called a "painterly view," extolling in their pictures and words the light, color, shadows and textures of faded Georgian buildings and cobbled streets. This cultural celebration of colonial Newport raised awareness and started an antiquarian movement that would play a vital role in the preservation of the 18th century city.

State House and Parade, drawn on stone by John Collins, printed by T. Sinclair's Lithography, Philadelphia.

State House and Parade, drawn on stone by John Collins, printed by T. Sinclair's Lithography, Philadelphia.

Life on Washington Square changed through the ages, bringing new types of activities, occupations and events to the place. Some of the grand houses of colonial merchants were adapted as various businesses while others were replaced by banks, commercial blocks, a hotel, a theater and gymnasium. The square became a place of public celebration as parades and block parties filled the streets on holidays.

5

The Modern Era

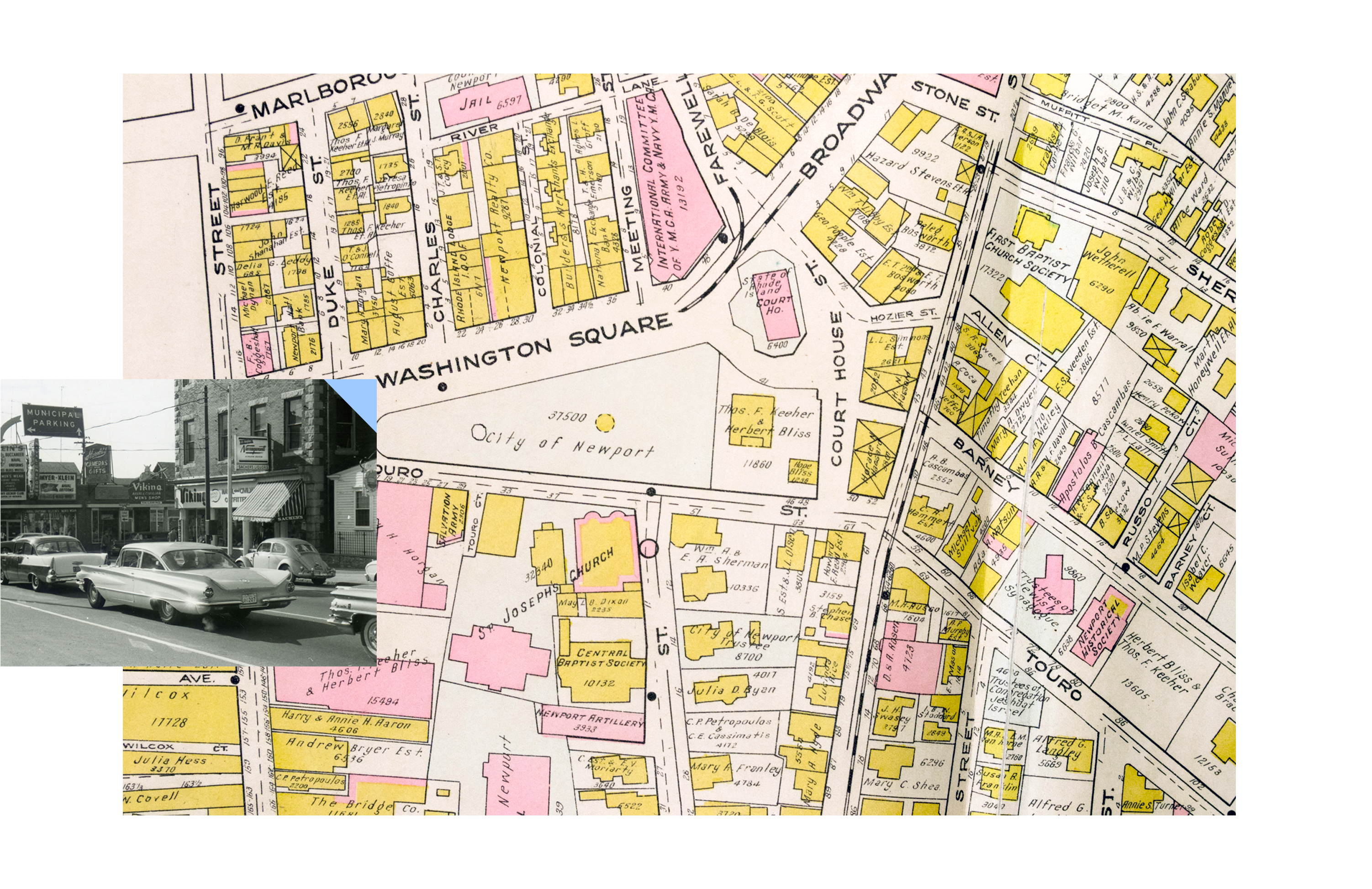

The 20th century visited dramatic change upon Washington Square. Economic decline arrived again with the Great Depression, followed by World War II and increased activity with Newport as the primary naval base for the North Atlantic Fleet. Washington Square became home to shops catering to naval personnel with bright lights and neon signs. The grand old Colony House and Brick Market survived, the anchors of the square, but they shared space with centuries of change.

The first city the vestiges of the early settlers..., the second city is the splendid 18th century town with memories of Washington, Rochambeau and Revolutionary glory; the third city contains what remains of a prosperous seaport along the wharves and docks of Thames Street."

— Theophilus North, Thornton Wilder, 1973

Thornton Wilder used the many layered history evident in the city's streetscapes in his novel Theophilus North set in the Newport of 1926. He compared Newport to ancient Troy with its many cities, one built on top of the other, a record of every past era. Wilder infused Newport with a tender humanity as his characters walk the streets, living out their ambitions, hopes and fears.

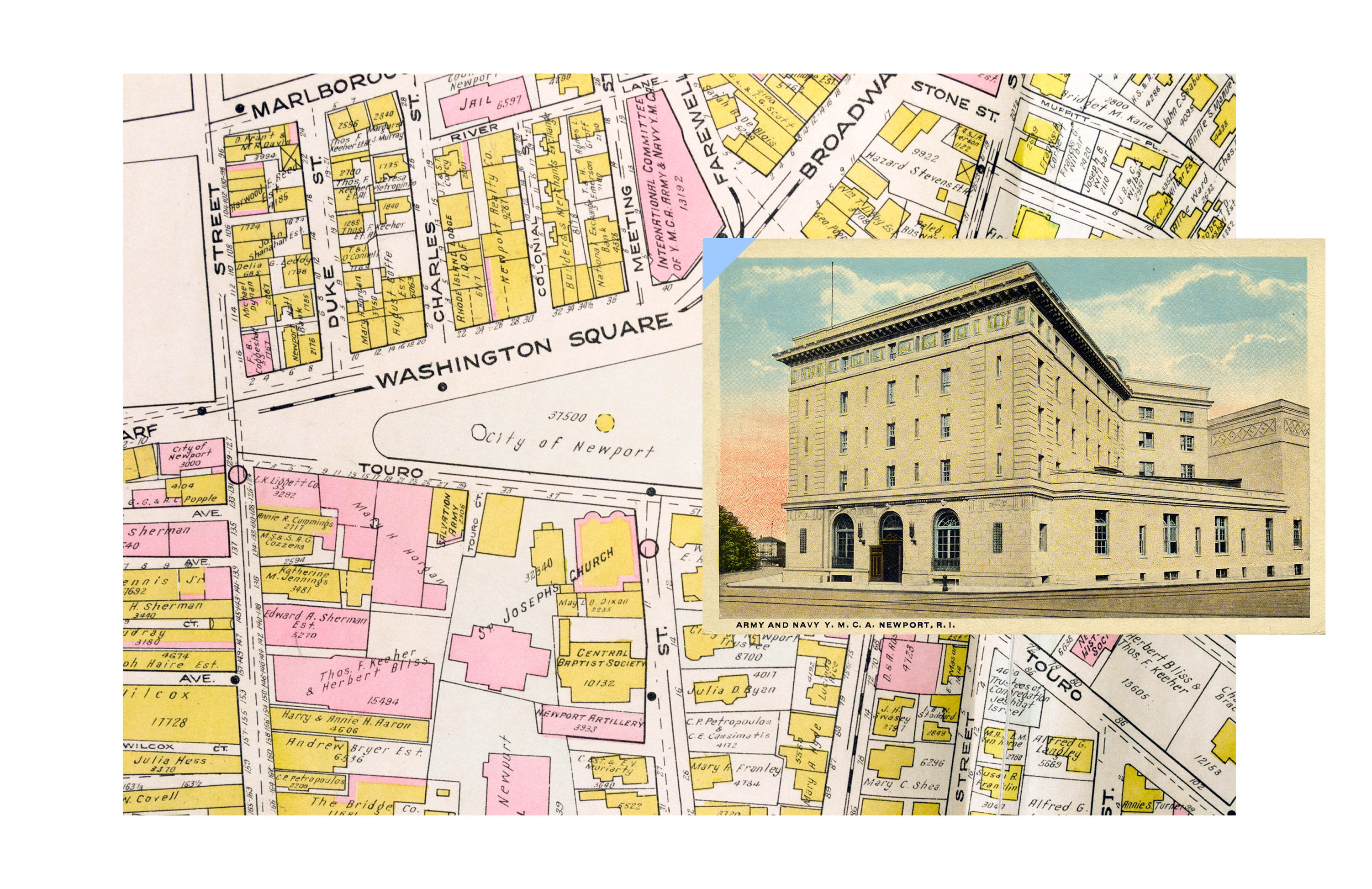

New construction continued to alter the face of the square in the early 20th century with the addition of the Army and Navy YMCA and the Court House. These buildings, however, were set within the historic framework of the area. By mid-century, the rise of Modernism in architecture and urban planning threatened the very existence of this time-worn urban space. Modernity had no patience for the picturesque effects of decaying buildings and crooked streets so often celebrated in earlier decades. Efficiency ruled the day. History was out. The future was in.

The Colony House and Brick Market, coming after the plan was set, make a focal point for Washington Square, but a square in name only. Instead, the town’s important buildings are scattered, presently a most interesting urban scene, and, at the same time, a challenge to the ingenuity of those who are trying to preserve it...surroundings of commercial blight are the rule rather than the exception in Newport.

— Report by Tunnard & Harris, 1960

6

Conclusion

The pageant of Newport's past and those who shaped it are embedded in the buildings and streetscapes of Washington Square. For over three and a half centuries, the square has thrived, decayed and revived. Many forces influenced the foundation and evolution of the square. The search for a new life, religious freedom, sea trade, revolution, industry, historic preservation and urban renewal all played a role in the creation of the "accidental work of art" that is Newport's great civic space.